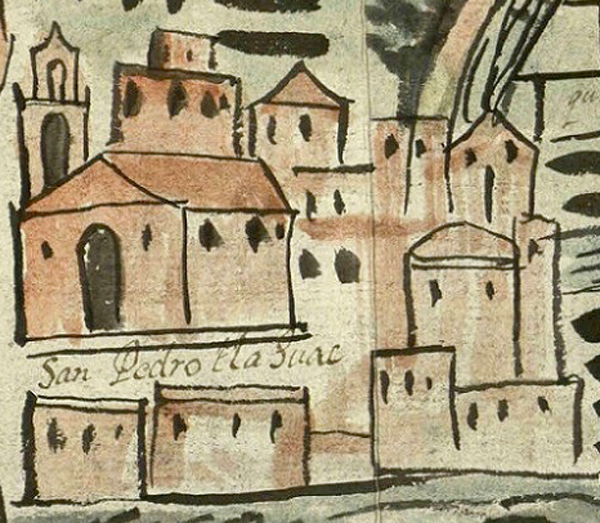

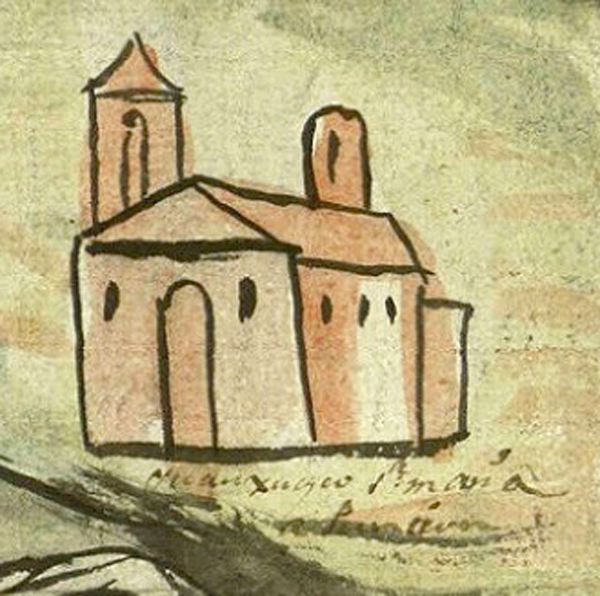

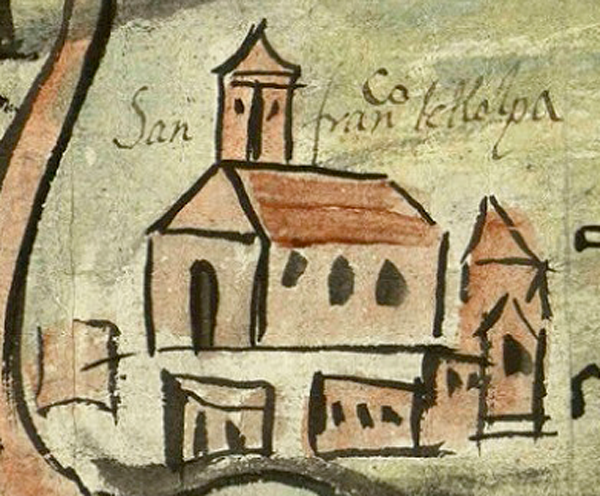

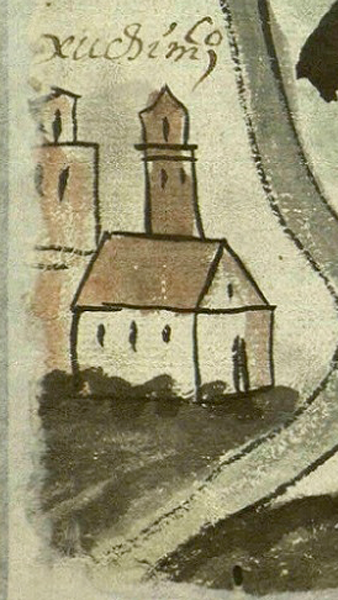

Richard Conway writes: This map is a reproduction of an earlier map that had been painted on a friary wall in San Pedro Tlahuac, a Nahua ethnic state (altepetl) located to the southeast of Mexico City. The copy was commissioned during a lawsuit between the residents of Tlahuac and the owner of a ranch. At issue before the court was the location of the ranch’s borders. While the case was being examined, friars from Tlahuac told the authorities that the map on their friary’s wall might help in resolving the boundary dispute. The judge ordered that a copy of the mural be made and entered as evidence into the record. The task of reproducing the map was entrusted to a man named Pedro de Sandoval—it is unclear whether he actually painted the map or not (it is unsigned)—but the copy was certified as having been made on January 7, 1656. The map, which is oriented with north at the top, shows Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco in the foreground. In the background is a peninsula that separated these two lakes from Lake Tetzcoco, which is out of sight and beyond the hills to the north. The ranch involved in the land dispute was located somewhere in the peninsula’s upland area. An enclosure containing livestock, perhaps sheep or goats—such as would be found on this type of ranch—appears at the top-center of the map. The landscape is also filled with roads and churches painted in red. Many of these churches served as emblems of communities and did not necessarily resemble actual structures. Some of the larger communities, such as Tlahuac, are shown with churches and other buildings. Tlahuac takes pride of place in the map not only as the home of the friary with the cartographic mural but also because it was a prominent altepetl, one that was located on an island in the middle of the lakes. Rather than being a single, calm expanse of water, the lakes are shown here as complex, modified environments, filled with swirling currents and zigzagging channels as well as many clusters of chinampas, the region’s famously productive raised garden plots of land. These gardens, which rose above the shallow lakes, are represented in the map as geometric sets of shaded rectangles. The making and cultivation of chinampas required extensive alterations to the environment. The Nahuas’ water management system included a dike connecting Tlahuac with the mainland, which had sluice gates beneath it and, as shown on the map, a road running on top. What look like roads traversing the lake, painted in blue, are instead water courses called acalotli. These channels were dredged and cleared from the lake to facilitate canoe-borne transportation and to integrate the chinampa districts into the wider region around Mexico City. With the inclusion of such distinctively indigenous artistic conventions as the whorls of water, the map reflects the perseverance of an ancient pictorial tradition even as it also provides us with a rare glimpse of the old aquatic world of the Aztecs. The reproduction of the mural map was drawn with ink and painted with watercolors on what appears to have been European paper that was folded. On the folio’s verso side, a document written in Spanish explains the origin and purpose of the map. To locate the paper version of this reproduction, go to the Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico (AGN): AGN Fondo Hermanos Mayo (Mapa 1155 or MAPILU #1155), Tierras, vol. 1631, exp. 1, cuad. 11, f. 96. In the AGN’s Mapoteca, it is pieza número 1155 in the Mapas Planos e Ilustraciones collection, located in planero 7, cajón 5. ---------- Editor’s note: The digital image for the Mapas Project has kindly been provided by the AGN and forwarded to us by Richard Conway. Ellen Heenan, at the University of Oregon, has processed the images using PhotoShop and has inserted them into our Filemaker Pro database so that they could be annotated (2015). This map has also been published in the April-June 2011 edition of Legajos: Boletín del Archivo General de la Nación, https://www.yumpu.com/es/document/view/47255208/consulta-este-numero-en-linea-archivo-general-de-la-nacion. Ver el estudio por Guillermo Sierra e Inés Ortiz, 113–114.

1 of 1